Framework for Growth

Understanding business leaders’ priorities for a renewed industrial strategy, and undertaking new economic analysis to assess the potential impact of improving the UK’s performance in key areas.

Raising productivity is critical in generating sustainable growth, by boosting output, living standards and tax receipts without fuelling inflation. But performance varies markedly across the UK. Overall, the most important reasons for the disparities in regional productivity are industry composition (for example, London's productivity is lifted by financial services) and variations in skills levels, labour activity and disposable incomes.

But progress is being made. Our analysis indicates that with the right investment and strategic planning, productivity can be increased across IM&S - helping to narrow regional divides. One of the most interesting findings is that some of the regions with relatively low productivity levels, such as Northern Ireland and Wales, have experienced significant productivity growth since 2011 and are now closing the gap on higher performing regions.

“Our Productivity Tracker points to the critical importance of investment in skills, technology and decarbonisation in driving regional productivity and sustainable economic growth. The big question is how to target the funding where it can have the greatest impact. Businesses will continue to take the lead in driving investment both individually and as part of regional clusters. But working closely with local leaders is also important in aligning strategies, planning and investment and creating the right conditions for lasting improvements in productivity and living standards."

Nick Atkin

Industrial Manufacturing and Services Leader, PwC UK

Our quarterly UK Productivity Tracker follows the UK’s productivity performance, and provides insight into sectoral and regional productivity. We draw on our own quantitative research, including data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), as well as our industry expertise and client insights, to offer broader perspectives on the UK's 'productivity puzzle'.

The primary focus is IM&S, which includes aerospace, automotive, engineering & construction, industrial manufacturing, legal & professional and business support services.

The latest ONS all-sector regional data is from 2021, while the sector-specific data within regions is from 2019. The analysis was carried out before the 2023 Blue Book (national accounts) revision.

Some of the least productive regions in the UK have also recorded the highest levels of growth in output per hour in recent years, showing regional gaps can be closed over time. For example, Wales was one of the two least productive regions in 2021. But it achieved the second highest growth in productivity (9.7%) between 2011 and 2021. Northern Ireland, also in the bottom half of the productivity rankings in 2021, saw an even bigger improvement in output per hour (13.5%), while the East Midlands followed with 6.7%.

Regions such as Northern Ireland and the East Midlands have benefited from some of the largest amounts of investment (measured by Gross Fixed Capital Formation as a share of GVA in 2020). If they continue prioritising investment and are successful in translating this funding into improved efficiency, they are likely to see significant boosts to their long-term productivity rates.

The productive potential of Northern Ireland and Wales has been buoyed by high performing cities such as Belfast and Cardiff. An important factor in Belfast’s and, more recently, Cardiff’s rising productivity is the presence of a City Deal, which gives local areas specific powers and freedoms to help them support economic growth, secure extra funding, create jobs or invest in local projects. Greater Manchester is among those to have also taken up the City Deal, improving its ability to coordinate planning and investment locally.

London leads the way for regional productivity overall with an output per hour of £51. With 7.9% of local employment in financial services (FS), the city’s strength in FS accounts for some of its standout productivity (output per hour of £84). If FS is stripped out, London’s output per hour drops by around 10%.

In other regions, FS has a much lower share of employment. Second after London is the North West, where FS represents a 3.4% share of employment. Across all other regions the share is below 3%.

However, there is much more to London’s success than FS. It’s the most productive region across a wide range of sectors, including construction, professional and support services within IM&S. London’s edge is rooted in high levels of investment, connectivity and access to talent that benefit all sectors. The key challenge for other regions is how to level up with London’s levels of productivity. Comparisons with France and Germany, where productivity overall is higher and the gap between cities and regions is much lower than the UK, show that such a country-wide uplift is possible.

Despite being middle of the road for overall productivity, Scotland had the highest manufacturing productivity of any UK region in 2019 with an output per hour of £46. However, growth in output was a more modest 5.2%, between 2010 and 2019.

Some of this outstanding performance stems from hydrocarbon processing in the wake of high oil prices. Scotland’s productivity lead and future potential is also rooted in its strengths in high value sub-sectors - including pharmaceuticals with 8.4% of GVA, more than 150 companies and 9,000 skilled professionals. Overall, Scotland’s manufacturing sector accounts for just over half of international exports, and 47% business expenditure on Research & Development (R&D).

As well as being second only to London in overall productivity, the South East had the second highest manufacturing productivity of the regions with an output per hour of £45. Though again, growth in output between 2010 and 2019 was modest at 4.3%.

The region’s standout productivity has been buoyed by its strength in high value areas, such as electronics (13.6% of GVA), pharmaceuticals (12.1%) and metals (9.6%). Thanks to its close proximity to London and significant concentration of talent and universities, the South East is the preferred location for many technology companies.

The East of England ranked fourth in overall productivity, and third in manufacturing with an output of £44 per hour. But manufacturing productivity in the region saw weak growth of just 1.6% between 2010 and 2019. The region’s largest manufacturing sub sector in terms of GVA is food & drink (13.4%), followed by machinery equipment (11.8%) and pharmaceuticals (10.8%). It also boasts Cambridge, one of the world’s most successful life sciences and technology clusters.

Our Tracker underlines the close relationship between above-average levels of productivity, talent availability and higher skills levels (specifically Level 3 qualifications such as A or AS levels, Level 3 NVQs and Diplomas, plus other further education and vocational qualifications).

The share of the working age population in French and German cities with high skills is significantly higher than in the UK. Good travel links also grant employers in French and German cities better access to available talent. This combination of access to skills and quality infrastructure has helped to fuel growth in high-skilled industries, raise productivity overall, minimise the gaps between different cities and regions and foster more balance in regional economic development.

“Broader and more even access to skilled talent locally is one of the main reasons why productivity in some major European cities is higher than in their UK counterparts. To boost productivity and bridge regional divides, the UK doesn’t just need extra investment in skills but also the high quality local housing and infrastructure needed to attract and retain key talent in less productive regions.”

Carl Sizer

UK Head of Regions & Platforms, PwC UK

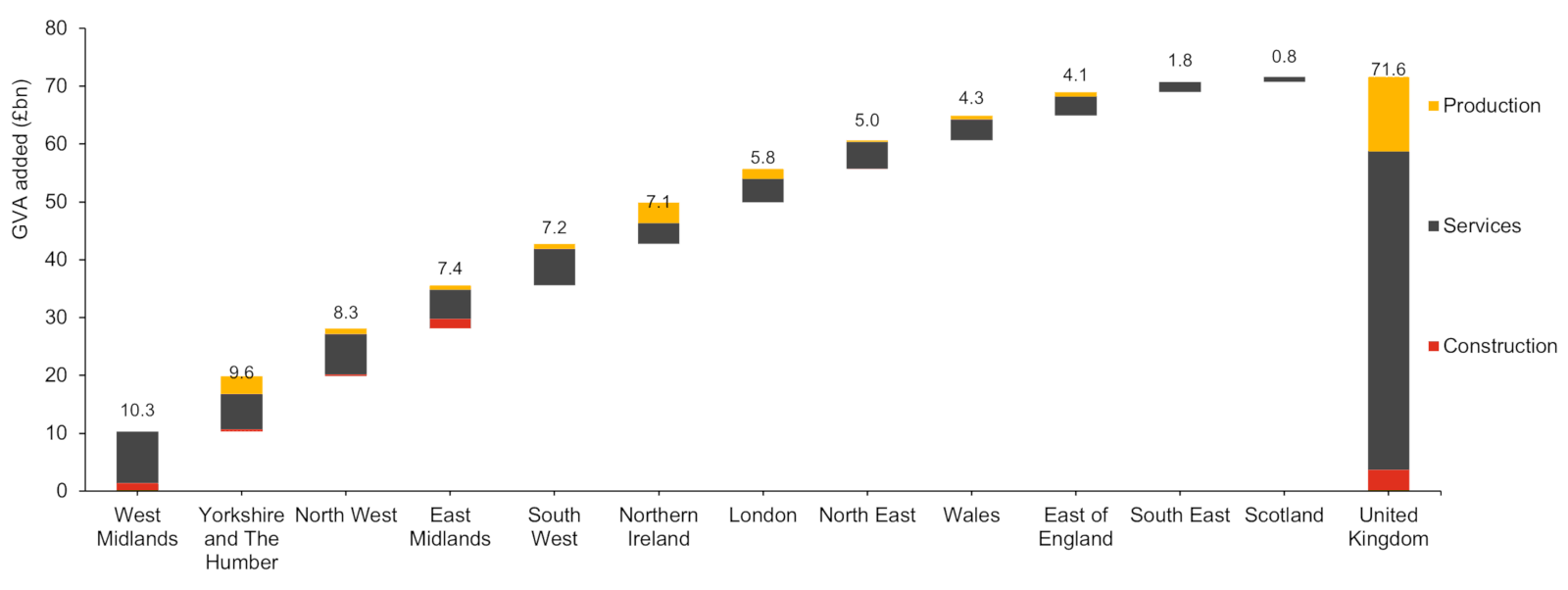

£71.6 billion

Our Tracker shows some of the regions with the fastest growing levels of productivity have benefitted from investment in housing, infrastructure and skills. Further drivers of growth include effective incentives for investment and close collaboration between businesses, technology providers and higher education institutions. These foundations have helped lagging regions catch up with more productive ones, boosting their prospects and efforts to bridge regional divides.

Our analysis also highlights the benefits of building on existing regional strengths in creating clusters of talent, enterprise and mutual support. But to realise the full potential, it's important to address the imbalance in disposable incomes regionally, much of which stems from differences in productivity and economic activity.

To help turn economic potential into productive growth, we believe the public and private sectors can work together more effectively, aligning strategies and planning policies and collaborating at a level that enables real change to be made.

Impact on regional GVA (£bn) if lagging regions raise their productivity to the industry’s median level, 2023

Source: PwC Economic Outlook September 2022

Prices in chained volume measure, 2018 £

Looking ahead, we believe there are three key ways to fire up regional productivity:

Industrial clusters can provide a valuable boost to regional productivity, quality job creation and growth. They attract businesses with common requirements and enable them to benefit from a shared pool of finance, expertise and skilled workers. This access to ideas and investment is proving especially valuable in accelerating innovation and decarbonisation.

Established clusters range from food production in the East Midlands to aerospace in the West of England and the life sciences Golden Triangle of London, Oxford and Cambridge. Meanwhile, the net zero agenda has opened up new opportunities across the country. The Humber is an interesting example: the most carbon-intensive region in the country, it is also home to the world’s largest offshore wind energy cluster. The Humber 2030 Vision seeks to build on the region’s net zero drive through £15 billion of investment in innovative areas such as green hydrogen production. Overall, the vision would see one in ten regional jobs safeguarded, with thousands of new jobs created.

The benefits of clustering are especially valuable within the IM&S sectors. By coming together in areas with strong grid capacity, for example, energy-intensive manufacturing businesses are able to access common resources and develop joint sustainability initiatives that would be costly to establish elsewhere.

To help establish, develop and benefit from clusters, local policymakers can identify the industries with the strongest potential in their areas, collaborate closely with anchor employers and tailor support accordingly. Developing core city hubs will also help drive investment and development across the wider region. Cardiff, for example, has a strong industrial base with a manufacturing GVA of £91,000 per worker compared to a UK average of £78,000. The city's partnerships with Bristol are helping to develop a wider regional cluster of skills, investment and strategic collaboration.

Regionally and nationally, mounting talent gaps are holding back productivity - and the challenge could worsen as skills demands evolve within the UK’s IM&S sectors. Nearly half of the UK's industrial manufacturing workers believe the skills needed to do their job will change significantly over the next five years, according to our latest Hopes and Fears survey.

The UK's low labour participation rate among workers aged 55 and over is among the trends exacerbating skills shortages. The UK lags behind a number of advanced economies on our Golden Age Index, ranking 21st across the OECD. The Index shows the employment rate for older workers is impacted by house prices, investment income and NHS waiting times, but there are also regional disparities - with the highest rate of employment in the South East and lowest in the North East.

Local government, educators and businesses need to collaborate to target specific regional talent needs, while aligning workforce skill sets with the demands of sectors, hubs and economic conditions. Together they can drive opportunity, productivity and inclusive growth by providing organisations with the talent they need and offering local people openings into better paid and higher quality employment.

Bristol, for example, demonstrates the link between home-grown skills and industrial success. At the centre of the UK's leading aerospace cluster, Bristol University offers one of the country’s leading aerospace engineering degrees, drawing significant funding and engagement from the industry. In turn, the university matches every student with an industrial mentor. Meanwhile, along with a aerospace engineering degree, the University of the West of England in Bristol also offers a ‘work while you study’ aerospace engineering degree apprenticeship.

Other examples include the Manchester Airport Group, which seeks to inspire the next generation of aviation professionals. Key features of the initiative range from fully accredited pre-employment training programmes to the introduction of a new decarbonisation-focused Jet Zero curriculum.

In the absence of a national industrial strategy, local governments and regional mayors are working with communities, businesses and educators to develop place-based strategic plans and initiatives, such as the previously mentioned City Deals.

The Cambridge Cluster, for example, has built-up around the university and its world class expertise and research in areas such as artificial intelligence (AI) and life sciences. The Cluster’s knowledge-intensive businesses employ more than 70,000 people and generate £21 billion in annual turnover. This benefits the wider East of England region, our Tracker shows, which has the highest level of investment in professional, scientific and technical activities in the country.

There has been considerable debate in recent years about how best to design and deliver regional and place-based strategies for growth. The notion of devolving these responsibilities to a city, local or hyper-local level has gathered momentum. Greater Manchester is frequently cited as the most established model in which both fiscal devolution and locally-developed and controlled strategies have supported collaboration and alignment between different public and private sector bodies, but there are many examples of similar activity right across the UK. While approaches might differ, the key is enabling stakeholders and decision makers to collaborate at a level of local power capable of driving real progress and change.

This collaborative approach can help businesses to take more of a lead in driving productivity by working with local leaders, educators and communities to address current and anticipated skills needs. As they expand, these strategies should focus on infrastructure development, including, for example, housing and transport hubs for the new employees they are looking to attract.

Understanding business leaders’ priorities for a renewed industrial strategy, and undertaking new economic analysis to assess the potential impact of improving the UK’s performance in key areas.

The Landing page of The Productivity Regional Trackers

A PwC report on how the radical reshaping of public and private sector roles would support UK cities respond to economic challenges

UK Employers must drive productivity and critical transformation while protecting against employee change fatigue and burnout