Download PDF -

Annual Law Firms’ Survey 2024

An annual survey of Top 100 law firms that focuses on the financial performance and key trends over the past year.

From detection and protection to response and recovery, stay ahead of cyber risk and build the resilience to take on change with confidence. Put cyber security at the heart of how you transform.

Driven by constant disruption and ever-changing risk, tech-driven transformation is now a perpetual business-as-usual state for organisations instead of a one-time hit. Putting cyber security at the heart of this essential change and reinvention is critical to gaining trust, protecting your organisation’s reputation and building the resilience to protect and create value.

Transformation and cyber security are inextricably linked, whether you’re digitising supply chains, building cloud-based business models or developing responsible and secure ways to innovate with generative AI. Your reliance on technology – its complex interdependencies and the cyber security risk it brings – means the impact of a cyber attack can be rapid and significant.

Keeping your employees and customers safe, and protecting your organisation’s prized information and assets, means staying ahead of cyber security risk, not just responding to it.

Through our deep technical cyber security expertise and breadth of business knowledge, combined with our powerful technology alliances, we help organisations across all industries embrace this change with confidence. From strategy to delivery to incident response and recovery, we can help you stay ahead of cyber security threats to protect value and unlock new opportunities to accelerate growth.

“As the way we live, work and connect with each other is increasingly digital first, cyber security must be embedded at the heart of everything we do. Only by working together to stay ahead of complex cyber risk can we protect and strengthen the values on which our society is built.”

Alex Petsopoulos,

Partner, Cyber Security, PwC UK

We’re at your side, working with you to safeguard customers’ data, your organisation, people and reputation. For cyber security that addresses today’s risks and provides a resilient foundation for growth, we have the technical knowledge and hands-on operational support you need.

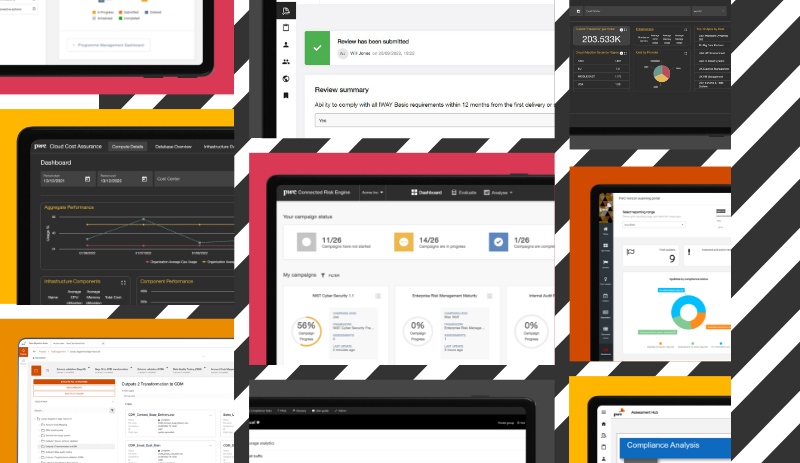

Today’s world is fast-moving, uncertain and unpredictable. Our digital products have been built to help better understand and navigate your business issues so that you can adapt and grow in the face of disruption.

Named a Leader in the IDC MarketScape: Worldwide Systems Integrators/Consultancies for Cybersecurity

Named as a Leader in the IDC MarketScape: Worldwide Cyber Security Risk Management Services 2023 Vendor Assessment

Identified as a Pacesetter in the ALM Intelligence Pacesetter Research, Cyber Security Consulting 2022

We’re empowering our clients to meet the demands of digital society through high trust cyber security services. By combining our expertise with our Alliance partners' technology most suited to their needs, we’re helping organisations solve their most critical business issues securely and embrace change with confidence.

Download PDF -

An annual survey of Top 100 law firms that focuses on the financial performance and key trends over the past year.

Download PDF -

Ensure the security and resilience of your critical infrastructure with PwC UK's Operational Technology Cyber Security services. Our strategy advisory experts provide comprehensive risk management, threat mitigation, and compliance support to protect your industrial control systems and secure operations. Learn more...

Download PDF -

Ensure the security and resilience of your critical infrastructure with PwC UK's Operational Technology Cyber Security services. Our strategy advisory experts provide comprehensive risk management, threat mitigation, and compliance support to protect your industrial control systems and secure operations. Learn more...

Download PDF -

Our podcast delves into the trending issues seen across organisations, bringing in perspectives of business leaders to explain how to go from issue to action.

Cyber Security Partner and Cyber Business Leader, PwC United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)7808 028337